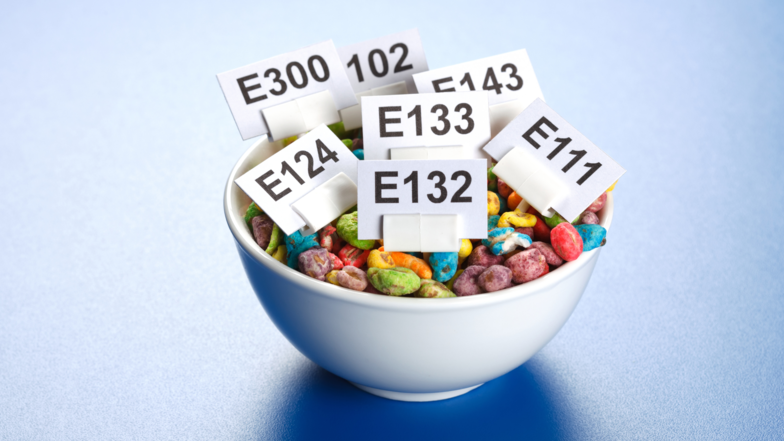

Lack of transparency in labelling (of additives): the techniques used by manufacturers to avoid the issue

An additive must be mentioned in the list of ingredients by its function followed by its name in words or its E number. This is of course unpopular with manufacturers, who try to create confusion by indicating either the E number or one of several names. For example, E150d is sometimes labelled as just caramel, sometimes as ammonium sulphite caramel, and sometimes with its own code… This makes it hard to keep track.

At the same time, additives often come in several versions depending on how they are obtained, which is something consumers know nothing about. This is the case with lycopene E160d, an antioxidant naturally present in tomatoes, which can be (i) synthetic, (ii) extracted from tomatoes using a solvent or (iii) produced from micro-organisms. It is found in vegetarian Knacki sausages listed simply as ‘colouring agent: lycopene’ with absolutely no indication of its origin.

So now we’re totally lost... How can such a system provide clear and legible information for consumers? And that’s not all!

Manufacturers also use an array of tools to circumvent the obligation to label additives:

- Processing aids: like additives, these substances are used for technological purposes, but are supposed to be limited to the manufacturing stage. Their use is not labelled on the final product, although residues may remain. Some manufacturers are taking advantage of this grey area, and in France, the Directorate General for Competition Policy, Consumer Affairs and Fraud Control (DGCCRF) is currently considering ways of clarifying the situation.

- Transfer additives: additives used in raw materials are not required to be labelled on the final product, but it is possible for the ingredient to act as a Trojan horse for the additive to have a more global effect on the final product.

- The ‘clean’ label: this technique, which has been a big marketing success in recent years, consists in replacing additives with plant extracts, plant fibres or other ‘ingredients’ that look natural but actually fulfil the same function as an additive (for example: acerola or citrus fruit extract as an antioxidant, cider vinegar extract as a preservative or milk proteins as a texturiser). From a regulatory point of view, these sometimes highly purified extracts have not been subjected to the same risk assessment as authorised additives, and this poses a real safety problem.

Finally, be careful not to be fooled by claims, labels or marketing which emphasise naturalness or tradition: these claims do not guarantee the absence of additives in the product, and the only way to be sure about it is to look at the list of ingredients. This is why foodwatch is calling for this listing to be made much easier for everyone to understand, so that consumers can make informed choices.

When legal additives have controversial effects on health: the limits of regulatory science

The example of titanium dioxide (E171)

The case of titanium dioxide is a perfect illustration of how an additive that was initially authorised, and therefore supposed to be safe, ended up being banned, first in France and then throughout Europe. The battle that led to this ban, and in which foodwatch took part, was a long and winding road. Back in 2009, the French health safety agency AfSSA, nowadays ANSES, warned about the missing safety data regarding the oral toxicity of nanoparticles in food. The accumulation of evidence, thanks in particular to the work of INRAE, France’s National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment, finally led France to ban the use of titanium dioxide in 2020.

In 2019, foodwatch and other European NGOs urged the Commission and Member States to extend the French decision to the whole of the European Union. But the political decision-makers continued to hide behind alleged scientific doubts, and it took another scientific opinion by EFSA in 2021 to finally follow the French position and ban titanium dioxide throughout Europe in 2022. What a waste of precious time at the expense of the precautionary principle.

And yet, back in 2016, EFSA was already highlighting a lack of essential toxicological data. This example illustrates that regulatory science must be progressive and reactive: what is deemed safe one day may turn out to be risky the next.

Other additives continue to be authorised despite a body of evidence indicating their harm to health

These include added nitrates and nitrites, against which foodwatch has been campaigning since 2019 along with Yuka and La Ligue Contre Le Cancer. Despite the fact that ANSES published a report in 2022 confirming the link between the risk of colorectal cancer and added nitrites and nitrates, no ban has yet been imposed at either national or European level. Meanwhile, products labelled ‘nitrite-free’ are flourishing on the delicatessen shelves, showing that doing without is possible. The battle goes on.

Several emulsifiers (certain gums such as E415 xanthan gum, E471 mono- and diglycerides of fatty acids, and E460-468 celluloses in particular) are in the hot seat due to a series of epidemiological studies showing a link between their consumption and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, disruption of the microbiota leading to chronic intestinal inflammation, and even an increased risk of developing certain cancers (colon, breast and prostate in particular).

A group of 6 azo dyes require the label ‘may have adverse effects on activity and attention in children’ to be placed in very small print on the back of the product (E102 tartrazine, E104 quinoline yellow, E110 sunshine yellow FCF, E122 azorubine, E124 ponceau red 4R, E129 allura red AC). A risk of carcinogenicity cannot be ruled out either.

Finally, there are intense sweeteners (such as aspartame E951, acesulfame K E950 or sucralose E955), for which there is no proven benefit in terms of weight control or metabolic diseases. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) even classified aspartame as ‘possibly carcinogenic to humans’ in July 2023, in line with the results of epidemiological and toxicological studies. There is no room for doubt when it comes to the risk of cancer, especially when it comes to substances whose usefulness is highly questionable: foodwatch is calling for the ban of these additives in line with the precautionary principle.

Ultra-transformation and the cocktail effect: a mode of action underestimated by regulatory science

Ultra-processed foods are ready-to-eat foods, the preparation of which involves numerous industrial processes and the addition of additives to adjust texture, taste or preservation. The presence of additives is one of their key characteristics. A growing number of epidemiological studies, such as those carried out by the Nutritional Epidemiology Research Team (EREN) of the French National Institute for Health and Medical Research (INSERM), suggest that people who eat a lot of ultra-processed foods are at increased risk of developing metabolic disorders, and that these foods may even increase the risk of developing cancer.

Chronic exposure to a cocktail of additives via ultra-processed foods is one possible explanation for the link with the diseases mentioned. Given the difficulty of assessing the interactions of over 300 additives, foodwatch supports a drastic reduction in their use in order to limit the risk of a cocktail effect.

What is foodwatch calling for?

1. Reinforce the application of the law and the precautionary principle

The implementation of the law must be strengthened, i.e. only authorise substances that have been proven to be harmless (i.e. that there is no risk), with the burden of proof resting with the manufacturers.

When in doubt, the precautionary principle must be applied (see box). When new studies reveal a new toxicity or there is a lack of data, the authorities rarely ban the substance outright, but simply ask for additional scientific evidence. If there are reasonable grounds to fear that an additive is dangerous to human health at the dose consumed, it should be (directly, even temporarily) banned until its safety is proven by independent scientific studies. A similar situation to that of E171 should not happen again.

What is the precautionary principle?

This key principle of the European Treaties and food legislation allows the authorities to take protective regulatory measures, potentially transitional, such as a restriction or ban, when the scientific evidence relating to a harm to the environment or human health is uncertain and the stakes are high. In such cases, the precautionary principle allows the authorities to take preventive measures without waiting for full scientific assessments in order to prevent sometimes irreversible negative effects.

2. Reduce the overall number of authorised additives

This would make it possible to control the potential cocktail effect and ensure better monitoring of authorised additives. In organic food, only around fifty additives are authorised, whereas other labels such as Demeter are further reducing the number. And yet organic distributors are not to be outdone in terms of the variety of products available.

The most high-risk additives, such as intense sweeteners including E951 aspartame, E249-252 nitrates/nitrites and azo dyes, should be banned as a matter of priority. This overall reduction in the number of additives authorised in our food must also be carried out with a more nuanced approach to whether or not they are deemed ‘necessary’. Are texturisers, emulsifiers and melting salts really ‘necessary’ , or do they simply compensate, at lower cost, for accelerated industrial processes and lower quality ingredients?

3. The labelling of the number of additives should be more transparent

All additives should be labelled with their E number and name so that they can be unambiguously identified. Functional ingredients should also be identified for their technological purpose and be subject to the same assessment as the additives they replace.