Definition: What is a ‘food additive’?

Food additives are regulated at EU level. The definition of a food additive is a substance which is not usually consumed as a food or used as an ingredient, but which is added to the recipe for a technological purpose at various stages of production (manufacturing, packaging, storage, etc.). These stages of production are directly linked to the industrialisation of our food supply and the issues of preservation, standardisation and cost optimisation that go with it. Note: in European regulations, flavourings are not considered as additives and have their own regulations.

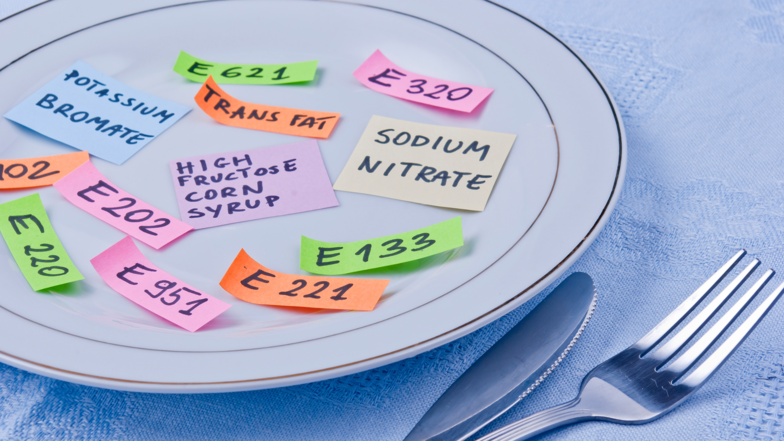

The food additives used in the EU

Around 330 food additives are authorised in Europe. They are grouped together in categories and each category has specific criteria on how they may be used and at what dosage. These food additives have various functions:

- to ensure food safety (preservatives, antioxidants)

- to provide a specific texture (thickeners, gelling agents)

- to modify the appearance or taste of the food (colourings, flavour enhancers, sweeteners)

- to guarantee recipe stability (emulsifiers, anti-caking agents, stabilisers)

Each additive has a code consisting of the letter E followed by 3 or 4 digits. The first digit of the code indicates the function: E1XX for colourings, E2XX for preservatives, E3XX for antioxidants, E4XX mainly for texture agents, E5XX for acidifiers, alkalis and hydroxides, E6XX mainly for flavour enhancers, E9XX mainly for coating agents and sweeteners and even E11XX for food enzymes and E14XX for modified starches etc.

In order to be authorised, an additive must meet a number of conditions and must:

- have no harmful effect on the health of consumers, according to the scientific evidence available;

- satisfy a sufficient technological need that cannot be met by other methods;

- not mislead the consumer;

- be of benefit in terms of consumption, whether this involves preserving the nutritional quality of the food or improving its organoleptic properties (its taste, colour or smell, for example).

Authorised additives may be of natural origin or synthetically produced. But be careful: natural origin only means that the additive is obtained from a natural substrate such as:

- plants (E100 curcumin from the herbaceous plant Curcuma longa)

- micro-organisms (E160a(iii) beta-carotene via fermentation)

- insects (E120 carminic acid, carmines from cochineal)

- algae (E400 alginic acid from brown algae)

Extraction techniques are then used to concentrate a specific substance that has little to do with the original ‘natural’ substrate, sometimes using solvents. The solvents authorised for extraction are specified and regulated, and some are indisputably toxic. This is the case with hexane, a petrochemical solvent authorised for the extraction of many dyes, which is toxic to human health (suspected reproductive toxicity) and the environment. Far from harmless!

Food additives in the organic and Demeter labels

The organic label authorises the use of only 52 authorised food additives. Specific conditions of use and restrictions may apply in addition to those for non-organic foods. Most of these additives are natural. Only four are of chemical origin. The Demeter label is intended to complement organic farming. It claims to use almost no food additives. In particular, nitrites E250-252, alginates E400, 401 and 402, carrageenan E407 and xanthan gum E415, which are permitted in organic farming, are banned. In these two cases, it should be noted that the ban on numerous additives does not prevent the production of a wide variety of products.

Is the safety of authorised additives guaranteed? A system full of loopholes.

In theory, Article 6 of European Regulation 1332/2008 specifies that additives must not, ‘on the basis of the scientific evidence available, pose a safety concern to the health of the consumer at the level of use proposed’. They are subject to a risk assessment by the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA). The agency provides the European Commission and the Member States with the scientific information they need to decide on the authorisation of additives and their levels of use.

An assessment system with critical flaws:

- the assessment process is too dependent on industry data: for many of the additives to be assessed, the publicly available data (regulatory studies or publications in scientific journals) are very limited, as EFSA itself admits. The agency therefore issues calls for data to industry, and bases its assessments primarily on these.

- assessments are often incomplete due to a lack of data: calls for data are often unsuccessful, both in terms of identifying the hazard (on criteria as important as endocrine disruption or DNA alteration) and estimating the consequences of exposure, particularly for young children. The risk assessment cannot therefore be carried out on all aspects.

- the requested tests only partially cover possible toxicities: long-term cumulative effects are underestimated, as is the cocktail effect resulting from exposure to multiple additives. Complex toxicities such as endocrine-disrupting effects or effects on the microbiota are not taken into account either, or are often not taken into account appropriately. Epidemiological studies, which are important for highlighting associations between exposure to multiple additives and pathologies in combination with toxicological studies, are not fully, or not at all, integrated into the risk assessment process, although EFSA says it is working on this. These studies must be given greater weight as a matter of urgency.

- the assessment process has long lacked transparency: because of the confidentiality of industry data, until 2021 it was not possible to have access to all the data used for assessment, nor to the weighting of studies used to draw up EFSA’s opinion. Coming into force in March 2021, a new European regulation now requires all studies submitted by the industry to be made available; it is a shame that most additives were re-evaluated before this requirement was introduced.

- additives are not re-evaluated on a regular basis: continuous monitoring and periodic re-evaluation of additives are necessary to incorporate new scientific findings and adjust authorisations. However, authorisations are granted without time limits, unlike for pesticides, for example. EFSA is mandated to re-evaluate additives when the European Commission deems it necessary, for example because of new scientific data. But there is nothing automatic about this process! In the case of E171 titanium dioxide, it took an accumulation of studies and even a ban on the colouring agent by France for the Commission to finally mandate a new assessment by EFSA. Meanwhile, a vast programme of systematic re-evaluation was launched in 2010 (see box).

- A protracted programme to re-evaluate additives

Not all of the 330 additives authorised to date have been evaluated by EFSA, since some were authorised before it was set up in 2003 by a committee reporting to the European Commission (the Scientific Committee on Food (SCF), which was disbanded in 2003). As mentioned above, there is no periodic re-evaluation of food additives, therefore a vast programme to re-evaluate all the additives authorised before 2009 was therefore launched in 2010. It was due to be completed in 2020, but has fallen well behind schedule, with 30% of the 315 additives authorised before 2009 still to be re-evaluated as of July 2024. How can this considerable delay be explained?

Admittedly, there is a lot of work to be done, and the need for additional data has arisen. But EFSA also points to the difficulties in accessing the data needed for a rigorous assessment, despite the calls for data sent out to professionals. In the absence of goodwill on the part of professionals, the authorisation of additives should therefore be suspended. However, some additives have been re-authorised by the Commission. The lack of financial resources for agencies such as EFSA is also a clear factor, resulting in a disturbing asymmetry compared to the resources of the manufacturers who use the substances they are responsible for assessing.